Parasitism is the most widespread life strategy in the living world. It could be said that parasites represent the largest group of species on the planet and are obviously an integral part of biodiversity. As Carl Zimmer says in his book Parasites (Capitán Swing, Madrid, 2016), a healthy ecosystem is full of parasites. Despite this apparent ubiquity, parasites are part of the “hidden biodiversity”, since our interest in them is mainly due to their pernicious effect on domestic animals, crops and humans, and because, due to their small size, usually go unnoticed. Even so, it is encouraging to note that, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in these organisms, not only because of their intrinsic value and their key role in the functioning of ecosystems, but also because of the intellectual fascination that they often arouse (think, for example, in how Plasmodium falciparum, which causes malaria, manages to evade our immune response over and over again, or how Toxoplasma gondii is able to modify our behaviour).

“We know that there are more than a dozen species of parasitic metazoans that, incredibly, live on the external surface of cetaceans such as the blowhole, the mouth corner, the eye socket or the urogenital orifice, all of them quite protected from currents”

There is added conservation interest in the case of parasites that infect endangered charismatic species such as cetaceans. In the Mediterranean Sea there are 8 species of cetaceans, 7 dolphins and a fin whale, whose parasitic fauna is known quite well thanks to the work in our marine zoology laboratory of the University of Valencia for several decades. The study of parasites in cetaceans is not easy due to the occasional nature of strandings, which prevents optimisation of sampling strategies.

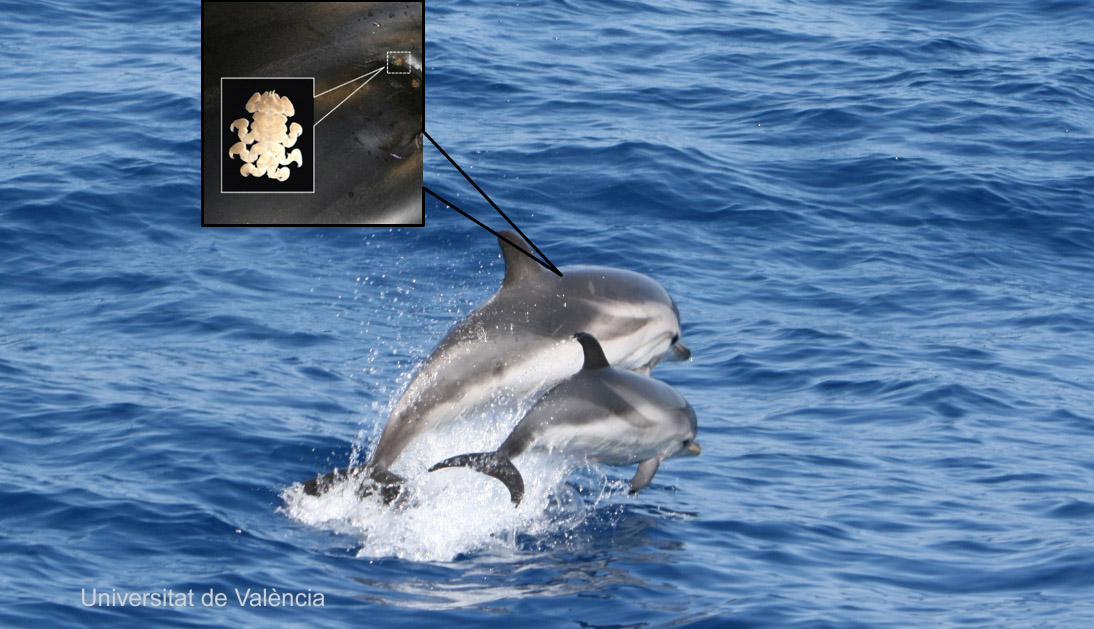

Furthermore, the oceanic character of many cetaceans makes any experimental study to investigate the biology of their parasites (for example, elucidate their complete life cycles) unfeasible. Even so, we know that there are more than a dozen species of parasitic metazoans that, incredibly, live on the external surface of cetaceans such as the blowhole, the mouth corner, the eye socket or the urogenital orifice, all of them quite protected from currents.

We also know that at least thirty species live inside cetaceans, in places as diverse as the digestive tract, lungs, kidneys, mammary glands, subcutaneous fat… even the penis. This “hidden” diversity was largely acquired after the ancestors of cetaceans colonised the marine environment. The evolutionary history of these associations is fascinating. Most likely, the vast majority of parasites of the terrestrial ancestors of cetaceans were not able to adjust their life cycles to the new aquatic environment and became extinct.

So where do the parasites that we currently find in cetaceans come from? The existing evidence, obtained in our laboratory during the last two decades, indicates that the parasites of cetaceans have a marine origin. In other words, the “protoparasites” colonised the cetaceans from hosts with which they coexisted in the sea. It is not surprising, therefore, that the majority of cetacean parasites are related to parasites of fish, seabirds, or pinnipeds (seals), with which the ancestors of cetaceans shared a habitat. The result is that the current parasite fauna of cetaceans is highly specific (in fact, we know in advance which parasites will appear in cetaceans stranded on the coasts of the Valencian Community).

The way to preserve this hidden biodiversity from parasites, in general, and from those that infect cetaceans in particular, is to consider them as worthy of conservation “rights”, as are other living beings with some degree of threat. Given the negative perception that we have about parasites, it may be an unsuccessful task to persuade society that parasites in danger of extinction should also enter conservation plans as well as their hosts. However, in addition to their intrinsic value, another of the positive dimensions of parasites is their use as natural markers to discover a multitude of biological aspects of their hosts such as their behaviour, diet, migration and distribution, etc. For example, a species of barnacle that attaches itself to the fins of dolphins has revealed previously unknown aspects of how dolphins swim. Scientists can help preserve both cetaceans and their parasites with the tools that we have, but we must also spread the intrinsic and applied value of these beings in society, beyond their pathogenic effect.

Mercedes Fernández Martínez and Francisco Javier Aznar Avendaño

Marine Zoology Unit

Cavanilles Institute of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology;

University of Valencia